The castle provided a formidable defense against attackers. But just as those attackers were forced to invent new ways to penetrate the walls, the defenders themselves needed additional strategies to defeat these new techniques.

- Walkways on top of the walls:

These allowed the defenders to move quickly to where the attack was coming from, and to easily fire downward at advancing soldiers.

- Gaps on top of the walls, and overhangs:

Gaps in the parapet allowed archers on top of the walls to shoot arrows and still remain somewhat protcted. In addition, the top of the wall often included an overhang, called a brattice, the floor of which had holes in it; boiling oil ('Greek Fire') or tar could be poured onto attackers trying to climb the walls.

- Moats:

These were dug in order to make it more difficult for miners to destroy a part of the wall from underneath. It also made it more difficult for attackers to climb the walls with ladders, especially if the moat was full of water. If it was, they could not swim across without being fired upon. (Most people couldn't swim anyway).

Attacking armies sometimes brought barges to ferry their soldiers across a moat. Some moats only surrounded parts of the castle; natural defenses protected the other sides. Quite often the moat was just a dry, deep ditch with steep walls, which by itself was very effective protection.

- Fortified entrance:

The main gate was often inside a building called a gatehouse. The doorway was protected by a drawbridge, and inside the gateway an iron portcullis, or set of bars, could be lowered. The walls of the gateway contained arrow slits for firing at the confined attackers from close range, and the ceiling contained murder holes for dropping rocks or burning liquids.

- Barbican walls:

The barbican was a short exterior wall protecting the entrance of the castle. It forced the enemy into a narrow space in front of the gate, where he made an easy target. Barbicans were sometimes also constructed with several walls forming a maze, whose twists and turns confused the attackers.

- Footings on the walls:

An angled footing at the base of a wall or tower, called a plinth or batter, was used to protect against undermining, and to cause dropped rocks to bounce horizontally toward the attackers. The footing also helped deflect a battering ram.

- Slits for archers in the walls:

These narrow windows were constructed with slanting sides so that each archer had a wide field of view.

- Walls within walls:

Later castles were built concentrically, with a larger, stronger wall inside the outer wall. Attackers who made it past the first one would find themselves easy targets inside a narrow courtyard. This technique was used right up until the late 1800's, when forts such as Fort Henry created a killing zone, with rifle fire between the walls.

- Projectile weapons:

Defenders also threw rocks with catapults, and dropped rocks on attackers who were attempting to scale the walls. They used crossbows, and the majority of the defending soldiers carried swords, or were longbow archers.

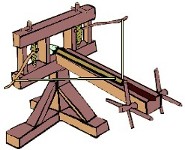

Another important weapon was the ballista. This was a gigantic crossbow, which fired huge arrows with great force. Using twisted ropes for storing energy, its arrows could penetrate several feet of wood, or several men. Its chief use was for disabling the catapults and trebuchets of the attackers.

- Towers:

Towers provided access to the walkways on top of the walls. They were also good lookout points, and were often constructed in spots that provided good vantage points for archers, eliminating blind spots. They could also be used as sleeping quarters for the soldiers.

Castles

|