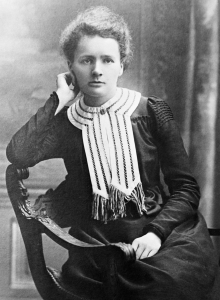

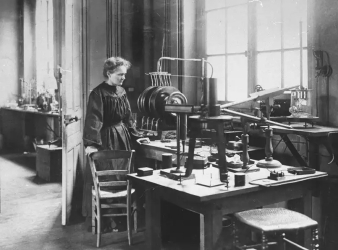

Marie Curie, née Maria Sklodowska, was born in Warsaw, Poland on November 7, 1867, the daughter of a secondary-school teacher. She received a general education in local schools and some scientific training from her father. In 1891, she went to Paris to continue her studies at the Sorbonne, where she obtained degrees in Physics and the Mathematical Sciences. There she met Pierre Curie, Professor in the School of Physics in 1894, and the following year they were married. She succeeded her husband as Head of the Physics Laboratory at the Sorbonne, gained her Doctor of Science degree in 1903, and following the tragic death of Pierre Curie in 1906, she took his place as Professor of General Physics in the Faculty of Sciences, the first time a woman had held that position. She was also appointed Director of the Curie Laboratory in the Radium Institute of the University of Paris, founded in 1914. Many exciting things were going on in the field of physics at this time.  In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen was studying the phenomena accompanying the passage of an electric current through a gas of extremely low pressure, and the resultant cathode rays. This led him to the discovery of a new and different kind of rays. He found that objects of different thicknesses placed in the path of the rays showed transparency when recorded on a photographic plate. When he immobilised the hand of his wife in the path of the rays over a photographic plate, he observed after development of the plate an image of his wife’s hand which showed the shadows thrown by the bones of her hand and that of a ring she was wearing, surrounded by the shadow of flesh, which was more transparent to the rays and produced a fainter shadow. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen was studying the phenomena accompanying the passage of an electric current through a gas of extremely low pressure, and the resultant cathode rays. This led him to the discovery of a new and different kind of rays. He found that objects of different thicknesses placed in the path of the rays showed transparency when recorded on a photographic plate. When he immobilised the hand of his wife in the path of the rays over a photographic plate, he observed after development of the plate an image of his wife’s hand which showed the shadows thrown by the bones of her hand and that of a ring she was wearing, surrounded by the shadow of flesh, which was more transparent to the rays and produced a fainter shadow. In further experiments, Röntgen showed that the new rays were produced by the impact of cathode rays on a material object. Because their nature was then unknown, he gave them the name X-rays. Later, others showed that they are of the same electromagnetic nature as light, but differ from it only in a higher frequency. Marie Curie would later study and make use of x-rays in her own research.  Meanwhile, the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in 1896 inspired the Curies in their research. The mineral pitchblende, (shown at left), rich in uranium, gave off more radioactivity than could be accounted for by the uranium in it. Meanwhile, the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in 1896 inspired the Curies in their research. The mineral pitchblende, (shown at left), rich in uranium, gave off more radioactivity than could be accounted for by the uranium in it. She decided that pitchblende must contain another element, highly radioactive, one that had never been seen before. They began to study the invisible rays that uranium emitted. Becquerel had shown how these rays could pass through solid substances, and cause air to create electricity. Within pitchblende Marie and Pierre uncovered another new element, a deep black powder that was significantly more radioactive than uranium. Pierre and Marie named this new, previously undiscovered element polonium (symbol Po, atomic number 84). They took the name from Marie's home country of Poland. Due to its high radioactivity, polonium is extremely dangerous to humans, and Marie eventually suffered chronic health issues from her exposure to radioactive materials.  To study the rays, Marie Curie used the fact that when uranium rays passed through the air near an electrical measuring instrument, the instrument detected a difference. She had right kind of instrument, a very sensitive and precise device, invented about 15 years earlier by Pierre Curie and his brother, Jacques. Marie used this "Curie electrometer" to make exact measurements of the tiny electrical changes that uranium rays caused as they passed through air. Great care was needed to get reliable numbers. As she measured the rays from different uranium compounds, she discovered that the more uranium atoms in a substance, the more intense the rays the substance gave off. Trying to see what was so special about uranium, she tested minerals containing other elements. She found that thorium compounds also gave off 'Becquerel rays'. To study the rays, Marie Curie used the fact that when uranium rays passed through the air near an electrical measuring instrument, the instrument detected a difference. She had right kind of instrument, a very sensitive and precise device, invented about 15 years earlier by Pierre Curie and his brother, Jacques. Marie used this "Curie electrometer" to make exact measurements of the tiny electrical changes that uranium rays caused as they passed through air. Great care was needed to get reliable numbers. As she measured the rays from different uranium compounds, she discovered that the more uranium atoms in a substance, the more intense the rays the substance gave off. Trying to see what was so special about uranium, she tested minerals containing other elements. She found that thorium compounds also gave off 'Becquerel rays'. Marie Curie also developed methods for separating radium from the waste products left behind once the uranium had been extracted, in order to study its properties ... therapeutic properties in particular. Marie Curie also developed methods for separating radium from the waste products left behind once the uranium had been extracted, in order to study its properties ... therapeutic properties in particular.Curie went on to develop ground-breaking research into radiography using x-rays. This led her during World War I to create portable x-ray machines, or 'Petite Curies', to see inside wounded or ill patient's bodies, allowing accurate operations to be carried out on the front line. These life-saving devices helped save the lives of millions of soldiers by locating bullets, shrapnel fragments, or fractures. She also made a vast contribution to the fields of cancer treatment. Throughout her life she actively promoted the use of radium to alleviate suffering. She retained her enthusiasm for science throughout her life and helped to establish a radioactivity laboratory in her native city. In 1929 President Hoover of the United States presented her with a gift of $50,000 to purchase radium for use in the laboratory in Warsaw.  Studying radium was exhausting work, involving hours of labour-intensive grinding, dissolving, filtering, collecting and crystallizing. Radium was even more dangerous than polonium. What Marie and Pierre didn't realize at the time was that their repeated contact with these harsh chemicals was making them extremely sick. Studying radium was exhausting work, involving hours of labour-intensive grinding, dissolving, filtering, collecting and crystallizing. Radium was even more dangerous than polonium. What Marie and Pierre didn't realize at the time was that their repeated contact with these harsh chemicals was making them extremely sick. The importance of Mme. Curie’s work is reflected in the many awards bestowed on her. She received many honorary science, medicine and law degrees and honorary memberships in societies around the world. Together with her husband, she was awarded half of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903, for their study into the spontaneous radiation discovered by Becquerel, who was awarded the other half of the Prize. In 1911 she received a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry, in recognition of her work in radioactivity. She also received, jointly with her husband, the Davy Medal of the Royal Society in 1903 and, in 1921, President Harding of the United States, on behalf of the women of America, presented her with one gram of radium in recognition of her service to science.  Marie Curie died in 1934 in Savoy, France of leukemia, triggered by her extensive close contact with dangerous radioactive elements. The Curies' eldest daughter Irene Joliot-Curie, who also became a chemist and physicist, won a Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1935 with her husband Frederic Joliot-Curie, for discovering artificial radioactivity. Marie Curie died in 1934 in Savoy, France of leukemia, triggered by her extensive close contact with dangerous radioactive elements. The Curies' eldest daughter Irene Joliot-Curie, who also became a chemist and physicist, won a Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1935 with her husband Frederic Joliot-Curie, for discovering artificial radioactivity.

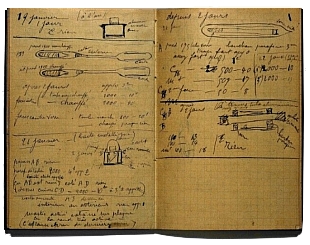

After more than one hundred years, much of Curie's personal effects, including her clothes, furniture, and laboratory notes are still radioactive. Regarded as national and scientific treasures, Curie's laboratory notebooks are stored in lead-lined boxes at Farance's Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. |