NASA and Johns Hopkins University in 2000 released the first colour image of Eros, the first asteroid ever orbited by a manmade satellite.

The Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) craft began obtaining a series of images from 210 miles (330 kilometers) above the surface hours after it began orbiting the Manhattan-sized asteroid. NASA and Johns Hopkins University in 2000 released the first colour image of Eros, the first asteroid ever orbited by a manmade satellite.

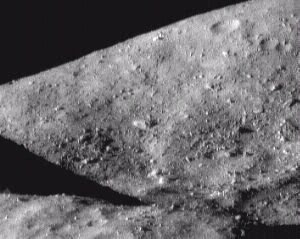

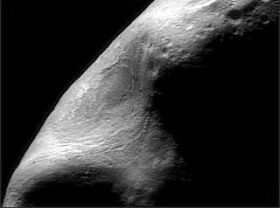

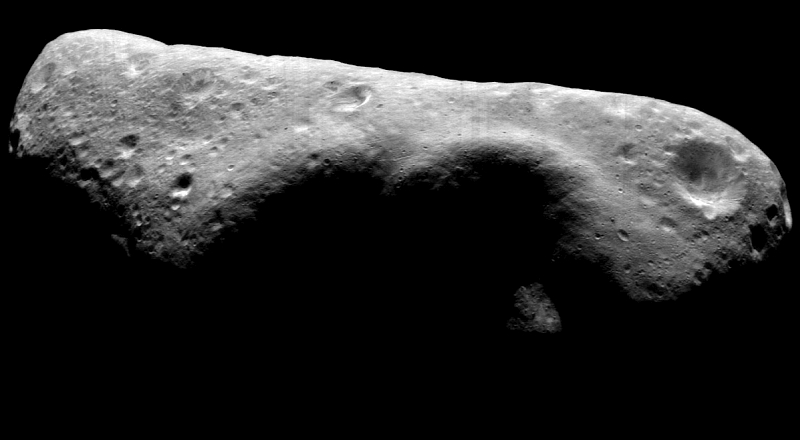

The Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) craft began obtaining a series of images from 210 miles (330 kilometers) above the surface hours after it began orbiting the Manhattan-sized asteroid.After a four-year journey to Eros, the craft began a yearlong close-up study of the asteroid, which orbits the sun at 160 million miles. Although Eros itself poses no threat to Earth, scientists hoped the $224 million mission would determine the asteroid's origin and offer clues about how to protect Earth from catastrophic collisions with other large space rocks.  Scientists speculated that the space rock may have broken off from a small planet eons ago. Only days into its yearlong orbit around Eros, the NASA robot ship snapped pictures that showed a panorama of boulders, bright spots and craters on the potato-shaped rock. Some of the images showed signs of geological layering, which suggests that Eros was once part of a much larger celestial body that broke up. The parent object was most likely smaller than the Earth's moon.  This picture was taken as the spacecraft passed directly over the large gouge that creates Eros' distinctive peanut shape. This picture was taken as the spacecraft passed directly over the large gouge that creates Eros' distinctive peanut shape. It is a mosaic of individual images, showing features as small as 35 meters across. The absence of large crater inside the gouge implies that the event that caused it to form happened more recently than the formation of the rest of the surface of Eros, according to NASA. Gravity on Eros is only about one thousandth of that on Earth. A human could easily jump off the surface. Yet the gravity on the asteroid seems strong enough to make boulders roll downhill, scientists said. Other mysterious features include a white spot 25 times brighter than other parts of surface, which indicates it could have a different mineral composition than the rest of the asteroid. The density of Eros is about the same as the Earth's crust. In contrast, Mathilde, an asteroid that NEAR zoomed by during its four-year trip from Earth, was hardly denser than water. The NEAR satellite began orbiting Eros from slightly more than 300 kilometers. But as the mission continued, it moved progressively closer to the asteroid, and eventually landed on its surface. Remarkably, the spacecraft – which was not designed as a lander – survived touchdown on the asteroid and returned valuable data for about two weeks. Last contact with NEAR was on Feb. 28, 2001, after which the spacecraft succumbed to the extreme cold.  Built and managed by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, NEAR was the first spacecraft launched in NASA's Discovery Program of low-cost, small-scale planetary missions.

Shown below is a view of the landing site taken just moments before the spacecraft touched down. Scientists have determined that most of the larger rocks strewn across Eros were ejected from a single crater in a meteorite collision perhaps a billion years ago. Before landing, NEAR Shoemaker orbited Eros for a year, taking thousands of high-resolution images of the 21-mile-long asteroid. From a composite map made of the surface, researchers counted 6,760 rocks larger than about 15 m across strewn over the asteroid's 1,125 square kilometers of surface. They found that nearly half of these rocks were inside the huge Shoemaker crater; most of the rocks of this size along the asteroid's equator appear to have been ejected from that crater.  |