The unmanned spacecraft Cassini, launched in 1997, has visited Jupiter and its moons (2001), Saturn and its moon Titan (2004) and photographed many of Saturn's other moons (2008).

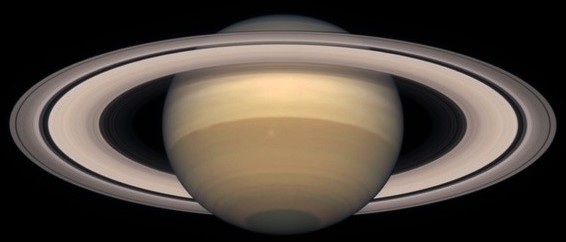

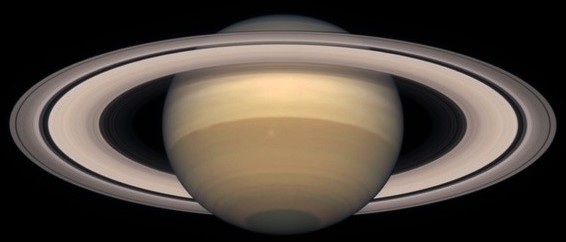

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun, and the second largest planet in our solar system. Its diameter is approximately 120,000 km (about 10 times the size of Earth). Saturn is flattened at the poles and bulged at its equator due to the extremely fast rotation of the planet; it spins once every 10 hours and 40 minutes (this is the length of its 'day'). Because of Saturn's great distance from the Sun, it takes almost 30 years to complete an orbit (this is the length of its 'year').

Saturn has no solid surface below its clouds; it is all atmosphere. It is composed mostly of hydrogen, along with small amounts of helium and methane. (Saturn is the only planet less dense than water; if a large enough ocean could be found, Saturn would float in it). Saturn is pale yellow, and has broad bands across its surface similar to those found on Jupiter. Saturn's atmosphere is very active; wind speeds can exceed 1000 mph (500 metres per second) near the equator.,

Saturn's rings make it beautiful to look at through a telescope. The rings are located from 6,630 km to 120,700 km above Saturn's equator. The ring system is actually composed of thousands of ringlets, including many gaps both large and small. Gaps are created due to resonances between the orbiting ring particles and the gravity of nearby moons.

Saturn's rings make it beautiful to look at through a telescope. The rings are located from 6,630 km to 120,700 km above Saturn's equator. The ring system is actually composed of thousands of ringlets, including many gaps both large and small. Gaps are created due to resonances between the orbiting ring particles and the gravity of nearby moons.

The rings' origin is not fully understood; one theory suggests they may have been formed from moons that were broken up by collisions with meteoroids, or by tidal forces. The rings appear to be unstable over millions of years, suggesting they were formed relatively recently (the solar system was formed about 5 billion years ago). The rings seem to contain a large amount of water; they may be composed of a mixture of ice, dust and rock, in chunks ranging from a few millimetres to several meters in size. Strangely, data from Cassini indicates that the rings have their own atmosphere, independent of Jupiter, which is mostly oxygen gas, a product of the ice in the particles that make up the rings.

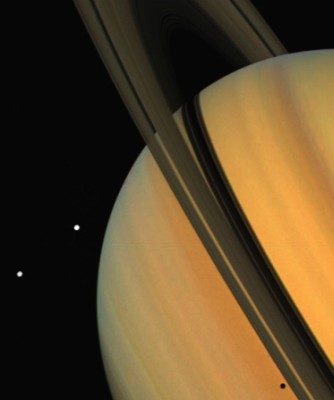

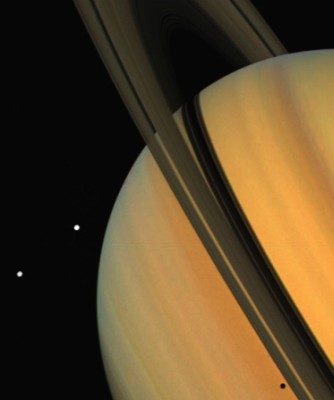

Much of our knowledge of Saturn came from visits by two unmanned space probes, Voyager 1 and 2, that passed by the planet in 1980 and 1981. (Voyager 1 is now leaving the solar system. Voyager 2 passed Uranus in 1986, Neptune in 1989, and is now also heading out of the solar system. Find out more about Voyager here). The photo at the right was taken by Voyager 1 in November 1980, from a distance of 13 million km. It shows Saturn with its rings and moons Tethys and Dione (and shadows of these on the surface of Saturn).

Saturn has more than 50 moons. When Cassini first arrived in the Saturn system it flew by the moon Titan. It has since made photographic surveys of some of Saturn's other moons. Here is some of what Cassini's visit to the Saturn system has shown us, along with photos taken by the spacecraft.

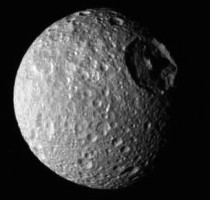

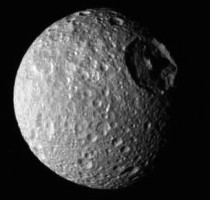

MIMAS

Mimas is made of ice and rock, with a huge impact crater on its surface. (The moon has been nicknamed 'Deathstar'). The surface might be the most cratered surface of any body in the solar system.

|

|

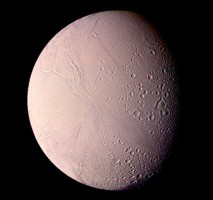

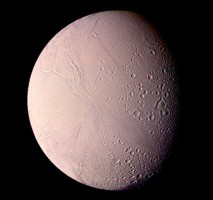

ENCELADUS

This tiny icy moon, only 500 kilometres in diameter, has a significant atmosphere near its south pole, whose source may be volcanoes on the surface or gases escaping from the interior. Cassini passed by Enceladus several times, confirming that this gas contains water vapour and organic compounds.

|

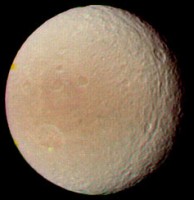

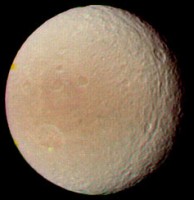

TETHYS

Tethys is one of Saturn's larger moons, and it is relatively close to Saturn. Tethys is composed mostly of of water ice, and has a large impact crater that covers most of the moon's surface. Two smaller moons, Telesto and Calypso, orbit Saturn just ahead of and behind Tethys.

|

|

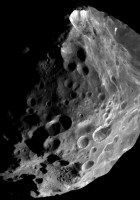

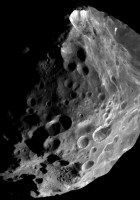

PHOEBE

Phoebe is about 220 kilometers across, and appears to be mostly ice, covered with a thin layer of darker material.

When objects hit the surface of Phoebe, they disrupt this surface layer and reveal the brighter ice beneath. In addition, some crater walls on the moon show evidence of surface sliding, again revealing the brighter undersurface.

|

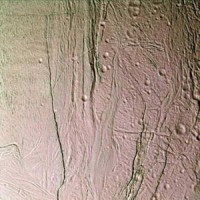

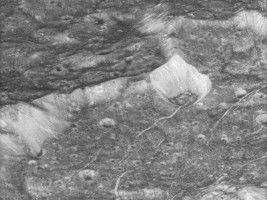

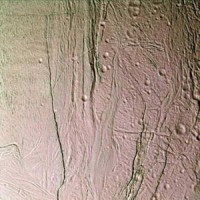

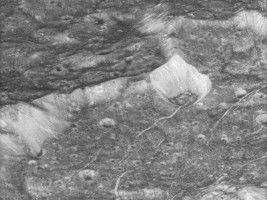

DIONE

Dione is composed mostly of water ice, but because of its relatively high density, much of its interior must also contain silicate rock .The image at the right, above, was taken by Cassini in October 2005 from a height of 4500 kilometres above Dione's surface. The photo shows a region of the surface that is about 23 km wide, a surface that is covered with craters, fractures, and grooves. The cause of the grooves and fractures is not known; especially fascinating are the parallel grooves running fom mid-right to lower left in the picture. Fractures visible on the floor of craters indicate that they were formed more recently than the craters they are in.

|

|

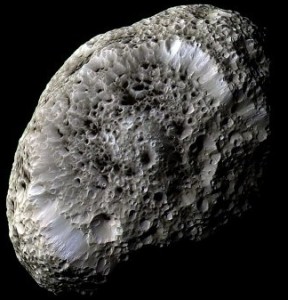

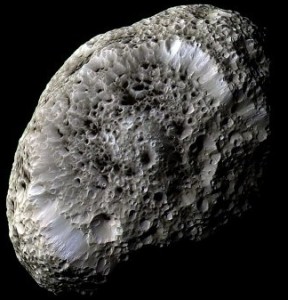

HYPERION

This amazing image (left) of the moon Hyperion was taken by Cassini in September 2005, from a distance of just 500 kilometres. The moon appears to be almost spongy; in fact, scientists believe that the moon is little more that a 'pile of rubble' containing a lot of empty space, and held together by its own gravity. Hyperion is just over 260 km long, and it spins erratically.

Solid carbon dioxide is also present on Hyperion, in a form that is attached to water ice. This is thought to be a possible cause for the porous or 'spongy' nature of Hyperion.

High-resolution photos taken more recently by Cassini suggest that the many craters contain layers of hydrocarbons on their floors. Hydrocarbons are organic molecules that are the ingredients needed for life; they have also been found in comets, meteorites, and galactic dust. When exposed to ultraviolet light, they can form even more complex molecules.

|

PROMETHEUS

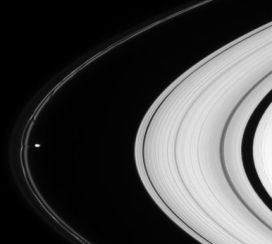

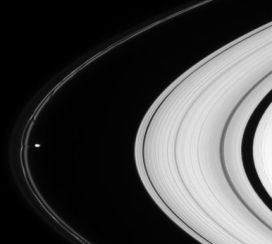

Prometheus' orbit lies within the ring system, and the moon is one of two that are referred to as 'shepherd moons' because of the effect of their gravitational pull on the nearby particles that make up the rings.

In the photo at the right you can see several effects of Prometheus' mass on the nearby F ring (one of the outermost rings). Prometheus is pulling material from the ring towards itself. Further along the ring you can also see the effects of prior encounters, where dark channels are left in the ring material.

Prometheus itself is just 102 kilometers across. The photo was taken in June 2007 by Cassini, at a distance of 2.1 million km.

|

|

|

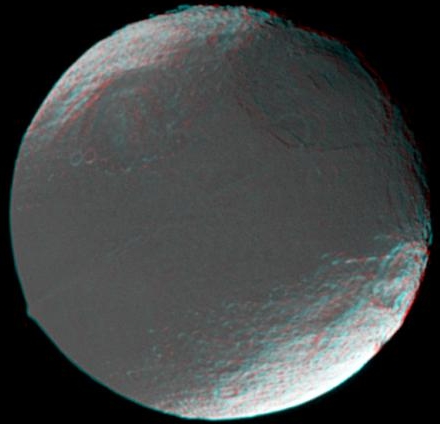

IAPETUS

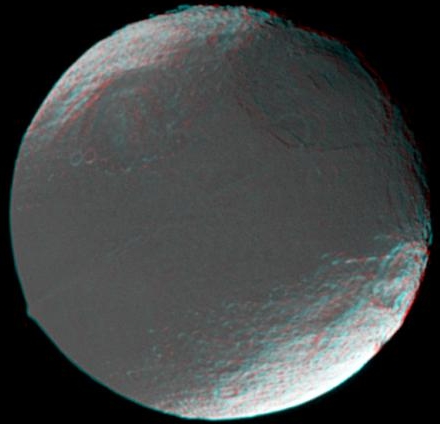

Iapetus is the third largest moon of Saturn. The stereo view of Iapetus seen at the left was created by combining two Cassini images, which were taken one day apart. The view serves mainly to show the spherical shape of Iapetus and some of the moon's topography. (You will need red-blue glasses to view the image in 3D; They can be ordered here.

North on Iapetus is towards the upper left. The prominent linear ridge in the center of the dark area marks the equator. The mountain on the left is part of the ridge, and rises at least 13 kilometers (8 miles) above the surrounding terrain.

The large basin at upper left was newly detected in these images. The crater at far right (within the bright terrain) was known from the days of NASA's Voyager missions.

|

The short movie at the right clearly shows that Saturn's rings form a very thin plane around the planet. The images were taken by Cassini as it crossed through the orbital plane of the rings, from the sunlit side to the unilluminated side. As the spacecraft moves northward, the angle of the rings decreases until they can be seen edge-on; then Cassini moves further north, and the rings from the unilluminated side can be seen for the first time.

Some of Saturn's moons can also be seen in this clip as they move around the planet. The first bright one is Enceladus; its slanted path shows clearly that not all the moons lie in the orbital plane of the rings. The bright moon near the end of the movie, moving from right to left, is Mimas.

This sequence of images was taken by Cassini in January 2007, at a distance of about 900,000 km from Saturn.

|

|

On Sept. 15, 2017, the spacecraft made its final approach to the giant planet Saturn. But this encounter was like no other. This time, Cassini dived into the planet's atmosphere, sending science data for as long as its small thrusters could keep the spacecraft's antenna pointed at Earth. Soon after, Cassini burned up and disintegrated like a meteor.

Watch an amazing video of the Cassini mission at Saturn here.

Resources

|

Saturn's rings make it beautiful to look at through a telescope. The rings are located from 6,630 km to 120,700 km above Saturn's equator. The ring system is actually composed of thousands of ringlets, including many gaps both large and small. Gaps are created due to resonances between the orbiting ring particles and the gravity of nearby moons.

Saturn's rings make it beautiful to look at through a telescope. The rings are located from 6,630 km to 120,700 km above Saturn's equator. The ring system is actually composed of thousands of ringlets, including many gaps both large and small. Gaps are created due to resonances between the orbiting ring particles and the gravity of nearby moons.