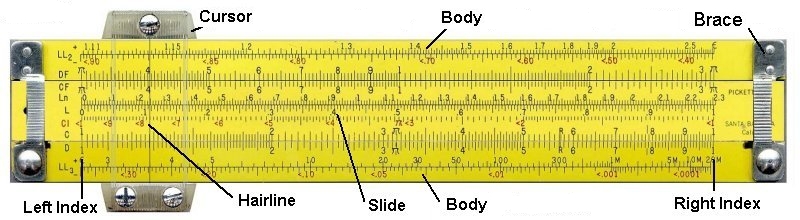

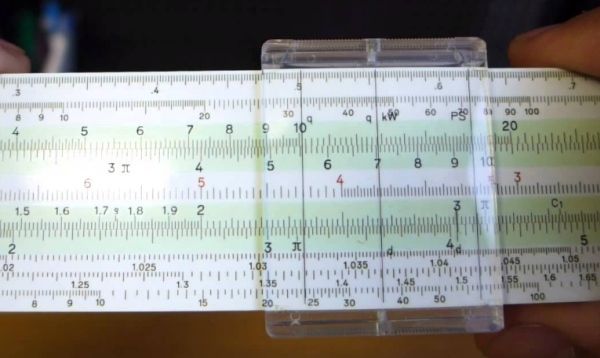

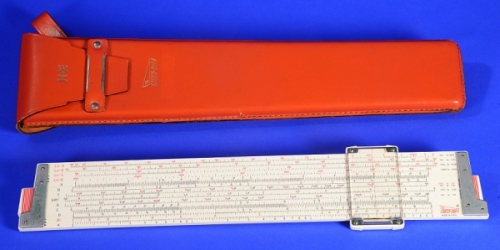

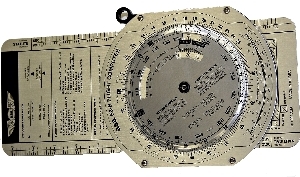

I found out recently that many people nowadays have no idea what a sliderule is. This is remarkable, considering that the engineers who made the lunar landings in the nineteen sixties and early seventies did most of their calculations on sliderules and very primitive computers. So I decided to rectify the situation by researching and writing a page about the sliderule. I used one in university, and when I started teachng in Toronto (about 1976) many math classrooms had a giant sliderule hanging over the front blackboard so the teacher could instruct students in how to use it. This is a sliderule:  I'll talk more about the specifics later; for now, you just need to know that is was a frame holding the non-moving body, with a sliding bar in the centre called the 'slide'. There was also a transparent sliding piece called a 'cursor' that had a 'hairline' that could be lined up on a number. Many different scales line the body and the slide. The slide and cursor were moved left and right to line up the numbers the user was entering, and to point to the answer. A sliderule was difficult to learn to use well, but once mastered, a confident sliderule user was just about as fast with a calculation as a modern user of a TI84 calculator. The problem was that the answers obtained from the sliderule were not very accurate, providing answers that were only three decimal significant digits, and the last digit was always a guess. Scientific notation was used to keep track of the order of magnitude of the results. A slide rule requires the user to separately compute the order of magnitude of the answer to position the decimal point in the results. For example, 1.5 × 30 (which equals 45) will show the same result as 1,500,000 × 0.03 (which equals 45,000). This separate calculation forces the user to keep track of magnitude.  The sliderule was used primarily for multiplication and division and for functions such as exponents, roots, logarithms, and trigonometry, as well as many others. English mathematician and clergyman Reverend William Oughtred and others developed the slide rule in the 17th century based on work on logarithms by John Napier. Before the scientific pocket calculator, it was the most commonly used calculation tool in science and engineering. The slide rule's ease of use, ready availability, and low cost caused its use to continue to grow through the 1950s and 1960s, even as electronic calculators and computers were being gradually introduced. The introduction of the handheld electronic scientific calculator circa 1974 made slide rules largely obsolete, and most suppliers stopped making them. Mathematical calculations were performed by aligning a mark on the slider with a mark on one of the fixed body scales. Numbers were aligned with the marks, with the cursor finding corresponding points on scales that were not adjacent to each other. This gave the approximate value of the calculated result. The user determined the location of the decimal point in the result, based on mental estimation. Scientific notation was used to track the decimal point in more formal calculations. Addition and subtraction steps in a calculation were generally done mentally or on paper, not on the slide rule. Traditionally slide rules were made out of hard wood such as mahogany or boxwood with cursors of glass and metal. At least one high precision instrument was made of steel. As plastics became available after WW2, sliderules began to be mass produced. Below is a popular model, the Keuffel & Esser Deci-Lon, a premium scientific and engineering sliderule. When I started university I was in the enineering program, and I and my fellow engineers bought this model, and proudly wore them hanging from our belts as we made our way around campus. Yes, we were all nerds!  (A few years later when I visited the campus at U of T, I watched engineering students walking to class with TI calculators in cases hanging from their belts!) Astronomical work required precise computations, and, in 19th-century Germany, a steel slide rule about two meters long was used at one observatory. It had a microscope attached, giving it accuracy to six decimal places. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the slide rule was the symbol of the engineer's profession in the same way the stethoscope is that of the medical profession. Many mechanical sliderule-type devices were created for special purposes. A common device like the one below was used by pilots to do vector calculations to determine a heading when there was a crosswind. I had one of these, and used in in ground school when I was learning to fly in the seventies.  German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun bought two Nestler slide rules in the 1930s. Ten years later he brought them with him when he moved to the US after World War II to work on the American space effort. Throughout his life he never used any other slide rule. He used his two Nestlers while heading the NASA program that landed a man on the Moon in July 1969. Aluminium Pickett-brand slide rules were carried on Project Apollo space missions. The model N600-ES owned by Buzz Aldrin flew with him to the Moon on Apollo 11.  The importance of the slide rule began to diminish as electronic computers, a new but rare resource in the 1950s, became more widely available to technical workers during the 1960s. The Hewlett-Packard company began producing hand-held devices that were programmable, and provided exponential and logarithmic functions, trigonometric functions, and hyperbolic trigonometric functions as well. The pocket-sized Hewlett-Packard HP-35 scientific calculator was the first handheld device of its type, but it cost US$395 in 1972.

The importance of the slide rule began to diminish as electronic computers, a new but rare resource in the 1950s, became more widely available to technical workers during the 1960s. The Hewlett-Packard company began producing hand-held devices that were programmable, and provided exponential and logarithmic functions, trigonometric functions, and hyperbolic trigonometric functions as well. The pocket-sized Hewlett-Packard HP-35 scientific calculator was the first handheld device of its type, but it cost US$395 in 1972. By 1975, basic simple four-function calculators could be purchased for less than about $100. In my first year of university, after I'd switched from Engineering into Math and Physics, a friend and I purchased one, and used it, along with our sliderules for more complex calculations, to help do the work assigned. We also rented it out on an hourly basis to others on our floor of the residence we were in! By 1976 the TI-30 scientific calculator shown at the right was sold for less than $25. Interested in how to use a sliderule? You can get online instruction in video form at https://sliderulemuseum.com/SR_Course.htm. Or just play with their virtual sliderule at http://www.antiquark.com/sliderule/sim/n909es/virtual-n909-es.html |