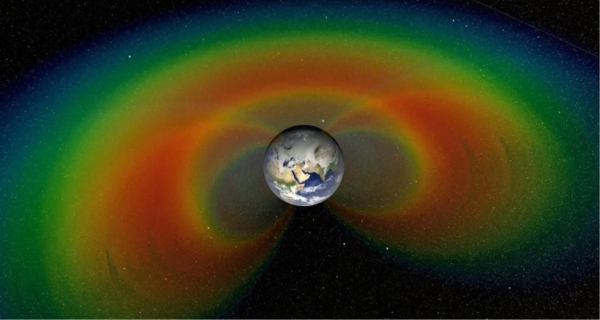

One of the largest hazards for astronauts traveling to Mars will be overcoming exposure to high energy radiation from our Sun's solar wind and solar storms, as well as galactic cosmic ray particles that originate outside of our solar system. This radiation is more damaging to humans than medical X-rays used to see broken bones or treat cancer. Fortunately for life on Earth, the Earth’s magnetic field traps and contains these high energy radiation particles and shields the Earth from solar storms and the constantly streaming solar wind that could damage technology as well as people living on the surface.  Located beyond low-Earth orbit, these trapped particles form two belts of radiation, known as the Van Allen Belts, that surround the Earth like enormous donuts. The outer belt is made up of billions of high-energy particles that originate from the Sun, and the inner belt results from the interactions of cosmic ray particles with Earth’s atmosphere. Located beyond low-Earth orbit, these trapped particles form two belts of radiation, known as the Van Allen Belts, that surround the Earth like enormous donuts. The outer belt is made up of billions of high-energy particles that originate from the Sun, and the inner belt results from the interactions of cosmic ray particles with Earth’s atmosphere. Astronauts laving the vicinity of Earth must fly though the Van Allen Belts, so it is important to fly through this region quickly to limit their exposure to radiation. Sensitive electronics on satellites and space craft traveling through the Van Allen Belts also need to be protected from the radiation. The Van Allen radiation belts were discovered in 1958 by James A. Van Allen, the American physicist who designed the instruments on board Explorer 1, the first spacecraft launched by the United States. He also led the team of scientists that studied and interpreted the radiation data. Prior to launch, scientists expected to measure cosmic rays, high-energy particles primarily originating beyond the solar system, which they had previously studied with ground- and balloon-based instruments. After receiving the data, Van Allen and his team began exploring the newly discovered radiation belts and their cause and effect. Although images of the Van Allen radiation belts make them look visible and colorful, this is actually just a representation. The radiation belts themselves are so dilute that astronauts don’t even see or feel them when they are outside in their spacesuits. In fact, scientists only detect them using sensitive instruments inside satellites and spacecraft.  Since 1958, scientists have continued to study the Van Allen radiation belts. In 2012, NASA launched the Van Allen Probes to study the region. Their job job is to determine how particles make their way in to the belts, where they disappear to, and what processes accelerate them to such high speeds and energies.

Since 1958, scientists have continued to study the Van Allen radiation belts. In 2012, NASA launched the Van Allen Probes to study the region. Their job job is to determine how particles make their way in to the belts, where they disappear to, and what processes accelerate them to such high speeds and energies. The Van Allen probes survived the extreme radiation for years, sending back a large amount of data. One key finding showed that the inner edge of the outer belt is highly pronounced. In 2019, the twin Van Allen Probes began their final phase of exploration, and will continue to use their instruments to send data to scientists on earth to study until they run out of fuel and eventually re-enter Earth’s atmosphere after about 15 years. In 1968, NASA’s Apollo Mission 8 was the first crewed spaceship to fly beyond the Van Allen belts to orbit the Moon and then return to Earth. The most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low-Earth orbit was in 1972, during the final mission of the Apollo program, Apollo 17. When the International Space Station was completed in 2011, its low-Earth orbit made it safer for astronauts to travel to and from the station as it is a shorter distance from Earth, approximately 400 kilometres, roughly the distance between Edmonton and Lethbridge. NASA plans to use its upcoming Artemis missions to send astronauts beyond the Van Allen Belts to land on the south pole of the Moon by the end of 2025, and eventually on to Mars. Since a one-way trip to Mars could take six to nine months, it is important to first develop technologies and conduct research on the Moon to better understand what is needed to survive in deep space. Since the Moon is more accessible to us than Mars, scientists can use it to gain important scientific knowledge about the effects of the harsh conditions of deep space on living systems. Altered gravity and high energy radiation exposure are just a few of the unique problems that need to be solved. |