Some creatures deal with the onset of winter by escaping the cold weather entirely, by moving south! Here are some well-known examples of living organisms that migrate south for the winter. Caribou  This large deer, also known as a reindeer, lives in the Arctic. Typical caribou habitat includes tundra (permanently frozen soil and few plants) and boreal forests (northern pine forests). The largest caribou subspecies is the woodland caribou, found in Canada and Alaska.

This large deer, also known as a reindeer, lives in the Arctic. Typical caribou habitat includes tundra (permanently frozen soil and few plants) and boreal forests (northern pine forests). The largest caribou subspecies is the woodland caribou, found in Canada and Alaska.

Caribou give birth in the relatively predator-free region of the extreme north, but those areas become completely inhospitable during the winter. So as the weather gets colder, the caribou and their young begin a long migration south. Theirs is one of the longest land migrations; they can travel over 4,800 kilometres a year between the northern tundra and the boreal forests further south. Monarch butterfly  In the summer, monarch butterflies live in North America, from southern Canada to the central and northern United States. They are most abundant in areas where the plant milkweed grows. Milkweed provides monarch caterpillars with nutrients, energy, and the chemical compounds that make the caterpillar poisonous to predators.

In the summer, monarch butterflies live in North America, from southern Canada to the central and northern United States. They are most abundant in areas where the plant milkweed grows. Milkweed provides monarch caterpillars with nutrients, energy, and the chemical compounds that make the caterpillar poisonous to predators.

The caterpillars pupate and eventually emerge as a new generation of butterflies in the fall, which head for Mexico to avoid the cold temperatures of winter. These late-season butterflies live up to eight times longer than their returning warm-season relatives, long enough to complete the trip to Mexico in a single generation. The trip back north, however, is a different story. Unlike migratory birds or whales, no one individual monarch makes the entire trip north. Instead, the trip up from Mexico is several generations long – these monarchs only live a few weeks, so they must breed and lay eggs on the way. Their young will continue the journey north. Canada Geese  The Canada goose is one of the most familiar geese in North America, where it is often seen in parks and other public areas. It can be recognised by its black neck and head, contrasting white cheeks, gray wings and white rump.

The Canada goose is one of the most familiar geese in North America, where it is often seen in parks and other public areas. It can be recognised by its black neck and head, contrasting white cheeks, gray wings and white rump.

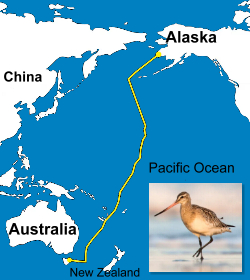

In the classic V-shaped migratory pattern, the geese fly south to Mexico and the southern U.S. for the winter, and then fly back north to Canada for the summer months. In recent decades, more and more geese have become non-migratory. These days, more than half of the Canada geese on the East Coast are year-round residents who never go to Canada or Mexico. Scientists think the decline in migratory behavior might be due to urbanization: Canada geese are very fond of city parks and suburban lawns, and they’re relatively safe from predators in human cities. So some geese may have given up migration to live year-round in the city. Bar-Tailed Godwit  The bar-tailed godwit is a long-legged wading bird whose migration is one of the most amazing of all animals. It migrates between Alaska and New Zealand. The bird spends summer in its Arctic breeding grounds. With the approach of winter, the bird migrates south. The total distance covered can exceed 12,070 kilometres!

The bar-tailed godwit is a long-legged wading bird whose migration is one of the most amazing of all animals. It migrates between Alaska and New Zealand. The bird spends summer in its Arctic breeding grounds. With the approach of winter, the bird migrates south. The total distance covered can exceed 12,070 kilometres! Even more impressive is the time the bird takes to travel this vast distance; one individual made the trip from Alaska to New Zealand in just 11 days! The bird probably lost half or more of its body weight during its continuous day and night flight. This is the longest-known non-stop flight by a bird, but also the longest journey without stopping to feed for any animal. If a godwit lands on water, it's dead. It doesn't have webbing in its feet, so has no way of getting off the water. One of the great mysteries in migration science is: how do these animals know where they're going? Do they navigate by the stars? Do they use landmarks? Recently scientists have discovered that some migratory birds have a magnetically sensitive protein in their eyes. The protein works just like a light receptor, but instead of light waves it picks up on magnetic fields. So these birds have a kind of compass built right into their visual system – they can literally see which way is north. |