When I was a teenager, and well into my twenties, I read a lot of science books, particularly ones dealing with astronomy, planetary science, and the possibility of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe. Science authors I read included George Gamow, Isaac Asimov, Wernher von Braun, Albert Einstein, Stephen Jay Gould, Jane Goodall and many others. However, the author who had the single biggest impact on my life was undoubtedly Carl Sagan.  He was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and professor. His best known scientific contribution was his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including the experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation. He assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them.

He was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and professor. His best known scientific contribution was his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including the experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation. He assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them.He supported the theory, which has since been accepted, that the high surface temperatures on Venus are the result of the greenhouse effect. As an honors-program undergraduate, Sagan worked in the laboratory of geneticist H. J. Muller and wrote a thesis on the origins of life with physical chemist Harold Urey. In 1954, he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts with general and special honors. In 1955, he earned a Bachelor of Science in physics. He did his graduate work at the University of Chicago, earning a MSc in physics in 1956 and a PhD in astronomy and astrophysics in 1960. Sagan spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies, and where he published more than 600 scientific papers and articles. He was the author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books.  He wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of Eden, Broca's Brain, Pale Blue Dot, and Cosmos, which became the best-selling science book ever published in English.

He also co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television. Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people in 60 countries. Sagan also wrote a science fiction novel, published in 1985, called Contact, which became the basis for a 1997 film of the same name. Sagan was a popular advocate of skeptical scientific inquiry and the scientific method. He pioneered the field of exobiology and promoted the search for extra-terrestrial intelligent life through a project called 'SETI'. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honours, including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction (for his book The Dragons of Eden), and for Cosmos: A Personal Voyage), two Emmy Awards, the Peabody Award, and the Hugo Award for science fiction. Sagan was an incredibly prescient writer, as evidenced from this passage from his book A Demon-Haunted World (1995):

A contemporary of Sagan's, author Isaac Asimov, had similar thoughts: "Anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge'.  Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program. From the 1950s onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA, where one of his duties included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions.

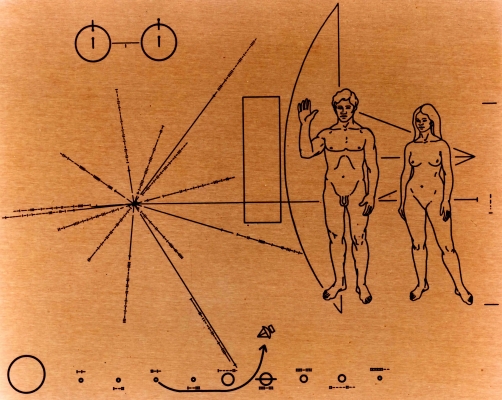

Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program. From the 1950s onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA, where one of his duties included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions. Sagan is most well known for assembling the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-plated plaque, attached to the space probe Pioneer 10, launched in 1972. Pioneer 11, also carrying another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record, which was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977. As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his conclusions on the surface conditions of Venus in 1962. Sagan was among the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface, and that Jupiter's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water, making Europa potentially habitable. Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft Galileo. The mystery of Titan's reddish haze was also solved with Sagan's help. The reddish haze was revealed to be due to complex organic molecules constantly raining down onto Titan's surface. Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions Sagan also perceived very early that global warming was a growing, man-made danger, and compared it to Venus' hot, life-hostile planet due to a runaway greenhouse effect. He testified to the US Congress in 1985 that the greenhouse effect would change the earth's climate system. Sagan was also well known for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including an experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation with physical chemist Harold Urey. He is also the 1994 recipient of the NASA Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare". (He was denied membership in the academy, reportedly because his media activities made him unpopular with many other scientists).  Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms, and was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This signaled a tremendous increase in the respectability of a then-controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the (now collapsed) Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms, and was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This signaled a tremendous increase in the respectability of a then-controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the (now collapsed) Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan also wrote the introduction for Stephen Hawking's bestseller A Brief History of Time. Sagan was also known for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions against pseudoscience, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction story. You can find a list of all of Carl Sagan's books here. As mentioned above, Pioneers 10 and 11 both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin, for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. The golden plaque was devised by Carl Sagan who wanted any alien civilization who might encounter the craft to know who made it and how to contact them. It gives our location in the Galaxy and depicts a naked man and woman drawn in relation to the spacecraft. Pioneer 10 is heading towards the star Aldebaran in the Taurus constellation, and will take more than two million years to reach it. Pioneer 11 is headed toward the constellation of Aquila (The Eagle). Pioneer 11 will pass near one of the stars in that constellation in about 4 million years. The Pioneer Plaque decription: The plaque is a physical, symbolic message affixed to the exterior of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft. At the core of this message is a fundamental concept that establishes a standard of distance and time, which, thereafter, is employed by the other components of the plaque. The design team postulated that hydrogen, being the most abundant element in the cosmos, would be one of the first elements to be studied by a civilization. With this in mind, they inscribed two hydrogen atoms at the top left of the plaque, each in a different energy state. When atoms of hydrogen change from one energy state to another - a process called the hyperfine transition - electromagnetic radiation is released. It is this wave that harbors the standard of measure used throughout the illustrations on the plaque. The wavelength (approximately 21 centimeters) serves as a spatial measurement, and the period (approximately .7 nanoseconds) serves as a measurement of time. The final detail of this schematic is a small tick between the atoms of hydrogen, assigning these values of distance and time to the binary number 1. Since Pioneer 10 was directed neither to an exoplanet nor a star, contact is extremely unlikely. However, if the spacecraft is intercepted by an alien species, there is at least a chance that the species can interpret the message. NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials. The Voyager message is carried by a phonograph record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Sagan. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind and thunder, birds, whales, and other animals. To this they added musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings from Earth-people in fifty-five languages, and printed messages from President Carter and U.N. Secretary-General Waldheim. Each record is encased in a protective aluminum jacket, together with a cartridge and a needle. Instructions, in symbolic language, explain the origin of the spacecraft and indicate how the record is to be played. The 115 images are encoded in analog form. The remainder of the record is in audio, designed to be played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute. It contains the spoken greetings, beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect. Following the section on the sounds of Earth, there is an eclectic 90-minute selection of music, including both Eastern and Western classics and a variety of ethnic music. Now that the Voyager spacecraft have left the solar system, they are in interstellar space. It will be forty thousand years before they make a close approach to any other planetary system. As Carl Sagan has noted, "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet." The following music was included on the Voyager record:

The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft:

Find out more about the golden record here. Watch a video about education: Carl Sagan discussing science education in the U.S. Carl Sagan was married three times and had five children. After developing myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62 on December 20, 1996. |

"Science is more than a body of knowledge; it is a way of thinking. I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority;

"Science is more than a body of knowledge; it is a way of thinking. I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority;