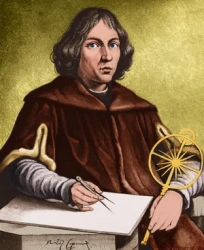

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Poland in 1473. An astronomer, he proposed that all the planets, including Earth, orbited the Sun. He also suggested that the Earth turns once daily on its own axis.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Poland in 1473. An astronomer, he proposed that all the planets, including Earth, orbited the Sun. He also suggested that the Earth turns once daily on its own axis.His idea that the Sun was the centre of our solar system, called the heliocentric theory, was proposed at a time when most people believed that Earth was the center of everything. Although his model wasn't perfect, it had important consequences for later thinkers of the scientific revolution that began with the Renaissance, including such figures as Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, and Newton. Eventually, other astronomers built on Copernicus' work and proved that our planet is just one world orbiting one star in a vast cosmos filled with both, and that we're far from the centre of anything. However, during Copernicus' lifetime and for the next few centuries, the belief that the Earth was at the centre of the universe, an idea based on the Greek astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy's view that had been unchallenged for 1500 years, was almost universally accepted. One of the problems with this model, once scientists began studying the heavens, had always been that some planets, on occasion, would travel backward across the sky over several nights of observation. Astronomers called this retrograde motion. To account for it, astronomers had incorporated a number of circles within circles - epicycles - inside of a planet's path. Some planets required as many as seven circles, creating a cumbersome model many felt was too complicated to have naturally occurred never mind the fact that there was no explanation for how it happened. In 1514, Copernicus distributed a handwritten book to his friends that set out his view of the universe. In it, he proposed that the center of the universe was not Earth, but that the sun lay near it. He also suggested that Earth's rotation accounted for the rise and setting of the sun, the movement of the stars, and that the cycle of seasons was caused by Earth's revolutions around it. He also proposed that Earth's motion through space was what was causing the retrograde motion of some planets across the night sky. Working in an era when the study of the skies was an undertaking meant solely to provide tables of motions of the planets to help astrologers make their 'predictions', Copernicus tried to come up with an explanation of planetary movement that accounted for observations. He postulated that, if the Sun is assumed to be at rest, and if Earth is assumed to be in motion, then the remaining planets have their periods of orbit increase from the Sun as follows: Mercury (88 days), Venus (225 days), Earth (1 year), Mars (1.9 years), Jupiter (12 years), and Saturn (30 years). This theory did resolve the disagreement about the ordering of the planets, but raised new problems. To accept the theory's premises, one had to abandon much of science as described by Aristotle that had been accepted as true for almost 2000 years, and develop a new explanation for why heavy bodies orbited the Sun, and that Earth itself was moving. Copernicus was working with many observations that he had inherited from ancient times, and whose trustworthiness he could not verify. Despite these limitations, and the unwillingness of the Catholic Church to accept the idea that the imperfect Earth should be at the centre of a perfect universe, Copernicus' theories eventually were vindicated. But not in his lifetime. Copernicus finished the first manuscript of his book, "De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium" ("On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres") in 1532. In it, he laid out his model of the solar system and the path of the planets. He didn't publish the book, however, until 1543, just two months before he died. The Church eventually banned the book in 1616. |