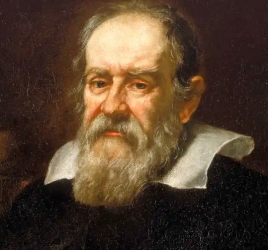

Galileo was born in the city of Pisa, in what is now Italy, in 1564. He was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath, and certainly one of the brightest minds of the Renaissance.

Galileo was born in the city of Pisa, in what is now Italy, in 1564. He was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath, and certainly one of the brightest minds of the Renaissance. Galileo has been called the father of observational astronomy, modern-era classical physics, and the scientific method. He was one of the first to state that the laws of nature are mathematical. According to Stephen Hawking, Galileo probably bears more of the responsibility for the birth of modern science than anybody else, and Albert Einstein called him the father of modern science. Galileo investigated speed and velocity, gravity and free fall, inertia, projectile motion, and he also explored technology. He described the properties of pendulums, after noticing that a swinging chandelier seemed to take the same amount of time to swing back and forth, no matter how far it was swinging. He invented the thermoscope and various military compasses, and used the telescope for scientific observations of celestial objects. He described the phases of Venus, and observed the four largest satellites of Jupiter. He viewed Saturn's rings, observed Kepler's amazing supernova, and analyzed lunar craters and sunspots.  In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua where he taught geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610. Based only on vague descriptions of the first practical telescope, Galileo made his own telescope with about 3x magnification. He later made improved versions with up to about 30x magnification.

In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua where he taught geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610. Based only on vague descriptions of the first practical telescope, Galileo made his own telescope with about 3x magnification. He later made improved versions with up to about 30x magnification. In 1610, while observing Jupiter, he saw four seemingly fixed stars nearby that changed their positions relative to each other over the course of many nights of observing. This caused him to come to the correct conclusion that they were not stars, but rather small bodies that were orbiting Jupiter. Galileo also noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. These four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, are now called the Gallilean Moons in his honour.  Galileo's observations of the satellites of Jupiter caused a controversy in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotle, who had held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth. He managed to convince some scientists, but many remained skeptical. Galileo continued to observe the satellites, and by mid-1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their orbital periods.

Galileo's observations of the satellites of Jupiter caused a controversy in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotle, who had held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth. He managed to convince some scientists, but many remained skeptical. Galileo continued to observe the satellites, and by mid-1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their orbital periods.Galileo's theoretical and experimental work on the motions of heavenly bodies, along with the work of Kepler and René Descartes, was a precursor of the classical mechanics developed by Sir Isaac Newton. Galileo observed the Milky Way, previously thought to be nebulous, and found it to be a multitude of stars packed so densely that they appeared from Earth to be clouds. He located many other stars too distant to be visible with the naked eye. He observed the double star Mizar in Ursa Major in 1617. Galileo was a proponent of heliocentrism, the idea first proposed by Copernicus that explained how the earth and other planets orbited the sun. Both his observations of the moons of Jupiter, and his descriptions of the phases of Venus, supported this belief. This idea, however, was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church; the matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that heliocentrism was foolish, absurd, and heretical, since, according to them, it contradicted Holy Scripture. He was tried by the Inquisition, found suspect of heresy, and forced to recant. His books were banned, and he spent the rest of his life under house arrest, where he continued to work. In 1638, Galileo described an experiment to measure the speed of light by arranging that two observers, each having lanterns equipped with shutters, observe each other's lanterns at a distance. The first observer opens the shutter of his lamp, and, the second, seeing that light, immediately opens the shutter of his own lantern. The time between the first observer's opening his shutter and seeing the light from the second observer's lamp indicates the time it takes light to travel back and forth between the two observers. Galileo reported that when he tried this at a distance of less than a mile, he was unable to determine whether or not the light appeared instantaneously. The speed of light, 300,000 kilometres per second, is of course too fast to be measured by such methods. Galileo is described as having dropped balls of the same material, but different masses, from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their time to fall didn't depend on their mass. This was contrary to what Aristotle had taught: that heavy objects fall faster than lighter ones, in direct proportion to their weight. While this story was probably a thought experiment by Galileo which did not actually take place, it was in fact a true description of how objects fall: "In the absence of air resistance, large and small objects fall at the same rate". Galileo in fact proposed that a falling body would fall with a uniform acceleration, as long as the resistance of the medium through which it was falling remained negligible, or zero when falling through a vacuum. He also derived the correct kinematical law for the distance traveled during a uniform acceleration starting from rest, namely, that it is proportional to the square of the elapsed time. See this experiment done in a modern facility with an amazing demonstration of a bowling ball and some feathers falling in a vacuum. During the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, astronaut David Scott showed that Galileo was right: acceleration is the same for all bodies subject to gravity, even on the Moon. |