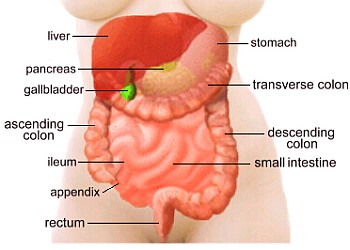

The large intestine is part of the digestive system, and joins the lower part of the small intestine (the ileum) to the anus. It is about 3.5 meters long. Most of the large intestine is made up of the colon, which has three parts: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, and the descending colon. Collectively these are also referred to as the large bowel.

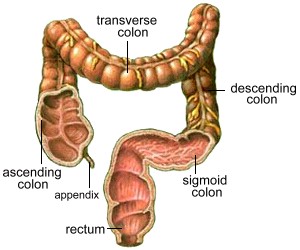

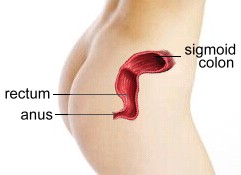

The large intestine is part of the digestive system, and joins the lower part of the small intestine (the ileum) to the anus. It is about 3.5 meters long. Most of the large intestine is made up of the colon, which has three parts: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, and the descending colon. Collectively these are also referred to as the large bowel.Where the ileum of the small intestine joins the ascending colon, there is a small side pocket called the cecum, tipped by the appendix. The other end of the large intestine is the rectum, a short canal which exits the body at the anus. The size of the large intestine in various animals is a reflection of their diet. Herbivores like cattle have a much more complicated intestine, while carnivores have a much simpler one. As omnivores, humans have a large intestine that is in between in relative size and complexity.

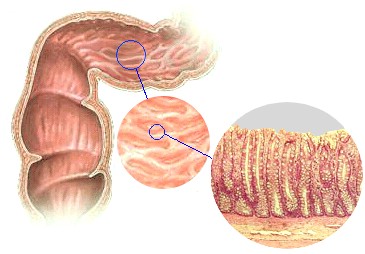

The colon, which makes up most of the large intestine, is much larger in circumference than the small intestine, which it surrounds in an arch. Inside it is covered with mucous, and its inner surface is convoluted; the surface itself is made up of deep channels called crypts; at the bottom of these crypts new cell growth occurs. The large intestine does not produce its own digestive enzymes, but instead contains large numbers of bacteria. These bacteria provide the enzymes to digest and utilize nutrients from whatever is left of the stomach contents after passing through the small intestine. This material already has had 90% of the water removed before it even enters the colon.  As the contents move through the colon, some of the little remaining water is removed by absorption, along with sodium and chloride ions. The inner surface of the colon secretes mucous, which not only protects it, but also helps bind the contents into a solid mass called feces and lubricate the feces' passage through the rest of the colon. The lining of the colon also secretes bicarbonate ions, which help to neutralize the acids produced by the bacteria. As the contents move through the colon, some of the little remaining water is removed by absorption, along with sodium and chloride ions. The inner surface of the colon secretes mucous, which not only protects it, but also helps bind the contents into a solid mass called feces and lubricate the feces' passage through the rest of the colon. The lining of the colon also secretes bicarbonate ions, which help to neutralize the acids produced by the bacteria.

Normal feces are about 75% water and 25% solids. The solids are mostly undigested organic matter, fiber, mucous and bacteria. The usual brown colour of feces is due to several chemicals which are produced by the bacteria as they break down the remaining nutrients. The feces' odour is caused by gases which are also produced by the bacteria, including mercaptans and hydrogen sulfide. Material that enters the colon is moved along its length and churned about by various processes. First of all, more material entering the colon from the small intestine provides some pressure to keep things moving. In addition, muscles in the various segments of the colon can contract, mixing and breaking up the material inside so it can be more easily absorbed. There are also muscle contractions which run along the length of the colon both ways to churn the contents, and help to move the material along.  Once or twice a day, these contractions move feces from the last portion of the colon, called the sigmoid, into the rectum, which is usually empty. Once or twice a day, these contractions move feces from the last portion of the colon, called the sigmoid, into the rectum, which is usually empty.As the rectum fills, the body's defecation reflex, a relaxation of both the internal and external anal sphincter, allows defecation through the anus. Defecation can of course be postponed, by intentionally constricting the external sphincter; this causes the internal sphincter to tighen also. The end product of bacterial digestion of cellulose and other carbohydrates in the colon is intestinal gas, not all of which can be absorbed by the colon; instead excess gas is passed through the anus. Intestinal gas is mostly nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide, hydrogen and methane. However, the characteristic odour of passed gas is due to small quantities of a few other substances, including hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans. Most of intestinal gas is the byproduct of bacteria breaking down material in the colon, especially material that the small intestine couldn't fully utilize, ... but some of it is also due to carbon dioxide produced from the interaction of various secretions, and air which is swallowed while eating. Bacteria in the large intestine also produce B vitamins, but these aren't absorbed; they're released from the body in the feces. This may explain the behaviour called coprophagy, or eating of feces, which is observed in rodents, rabbits and other animals. It may be a behavioural adaptation that allows them to recover these valuable nutrients. |