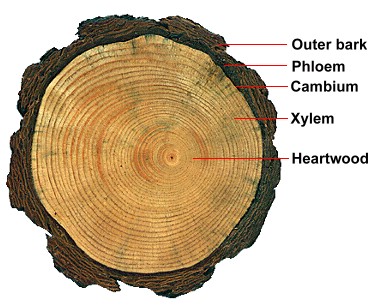

The trunk of a tree serves many purposes. The tough fiber tubes made from cellulose that form the trunk provide support. The dead outer bark provides protection from weather, insects and other damage. Inside the trunk, various parts of the wood transport nutrients and water, move the food made by the leaves back down to all the branches, and provide new wood growth year after year. Let's look inside the trunk at the various layers. We'll name them and describe what each layer does.  Outer Bark ... this is what you see from the outside. This layer protects the tree from insects, disease, extremes in temperature, and other damage.

Outer Bark ... this is what you see from the outside. This layer protects the tree from insects, disease, extremes in temperature, and other damage.

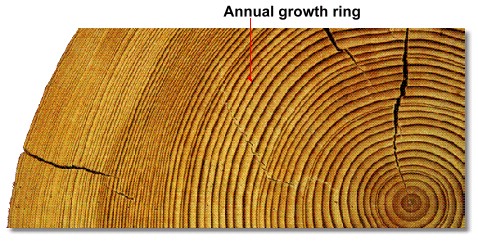

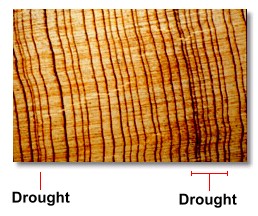

Phloem ... the inner bark. It carries sugar (carbohydrates) made by the leaves down to the rest of the tree, where it is converted into food that the tree needs to grow. Cambium ... this is a layer of cells just one cell thick, inside the inner bark, that is actively growing. The cambium makes xylem and phloem cells. As new phloem cells are made, the old ones dry out, adding to the bark. On the inside of the cambium, newly fashioned wood cells add to the sapwood (xylem). This is where growth occurs each year. Xylem ... this is the sapwood, where sap (water, nitrogen and minerals) is carried up from the roots to the leaves. Sapwood, composed of long cellulose molecules, gives a tree its strength . It also allows the tree to store starch that can be used to keep the tree alive when it is not making food. Heartwood ... in older trees, as new growth rings of sapwood are formed from the outside, inner rings of older sapwood, blocked with resins, become heartwood. Heartwood can no longer carry fluids, but its stiffness helps support the tree at the centre. Heartwood is generally darker than sapwood.  Each year, a new layer of sapwood is added. A ring forms which is lighter in the spring, turning darker as summer progresses. Each of these rings, light on the inside and dark on the outside, represents a single year of growth.  You can find out how old a tree is by counting its rings. Because trees can be many times older than we are, growth rings tell a story about the climate of the region in the distant past. Droughts, wet seasons, injuries, and forest fires can be seen in the variable growth of tree rings. The good years and the bad years are seen in the relative width of the rings.  For example, a wide ring indicates a year when the tree grew a lot. There was plenty of moisture, it was warm, and there were no insect pests or diseases. For example, a wide ring indicates a year when the tree grew a lot. There was plenty of moisture, it was warm, and there were no insect pests or diseases. Many wide rings near the center of the tree indicate that it had plenty of sunshine, water and nutrients when it was young, and little competition from other trees. Narrow rings indicate years when the tree hardly grew at all, perhaps because of bad weather or lack of rainfall (drought). Many narrow rings when the tree was young might indicate that there were a lot of other trees nearby competing for the available moisture and nutrients. Rings that are elongated hint that the tree grew on a slope, or grew around some sort of obstruction.  The presence of covered-over wounds in the rings can tell you when there were fires, insect or disease attacks, or other damage to the tree. Because each ring represents one year, you can determine the exact year when the damage or poor weather occurred.

The presence of covered-over wounds in the rings can tell you when there were fires, insect or disease attacks, or other damage to the tree. Because each ring represents one year, you can determine the exact year when the damage or poor weather occurred.

This history record is amazingly old ... the oldest living tree (a Bristlecone pine) is more than 4000 years old, which means we can examine its rings to see what the weather and growing conditions were like in that area for any year we want, right back to 4000 years ago! Giant redwoods and sequoias, while not quite as old (3000 years) provide similar data. It isn't necessary to kill a tree to examine its rings. By drilling to the centre of the tree and removing a pencil-thin core, the ring history can be easily seen, with little harm done to the tree.

The study of tree rings is an integral part of various sciences:

|